The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit shook things up on May 23, 2024, with an en banc panel (the first since 2018) overruling a decades-old test for determining the validity of a design patent. LKQ Corp. v. GM Glob. Tech. Operations LLC, __ F.4th__, No. 2021-2348, 2024 WL 2280728 (Fed. Cir. May 21, 2024). The court held that the Rosen-Durling test, which was established in the 1990s, was “improperly rigid” and instead utilized the framework established by Graham v. John Deere, which is the obviousness standard imposed for utility patents.

Previously, design patents were examined for nearly exact matches only, with the Rosen-Durling test requiring a reference to be “basically the same” as the claimed design and that any secondary reference be “so related” to the primary reference that the features in one reference would suggest application of those features to the other reference. In re Rosen, 673 F.2d 388 (CCPA 1982) and Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co, Inc., 101 F.3d 100 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Whether the design is “basically the same” depends on the visual impression created by the patented design as a whole. Id at 391. The Federal Circuit felt that this test was overly rigid and inconsistent with Graham and KSR. Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966), KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, 550 U.S. 398 (2007).

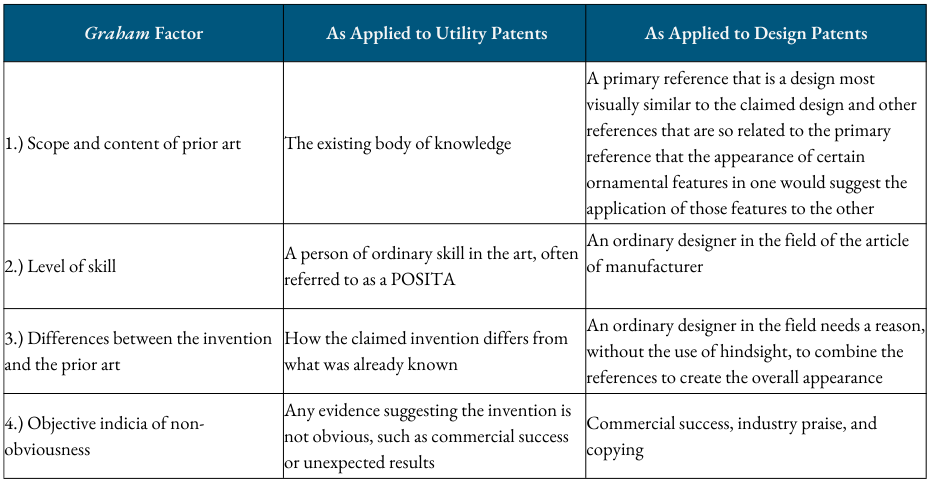

Graham set forth a four-factor test to determine obviousness in a highly fact-based analysis. The chart below shows how that can be applied to both utility patents and design patents.

383 U.S. at 17–18.

When applying the Graham framework to design patents, part one looks to the analogous art and a primary reference that is “the closest prior art, i.e., the prior art design that is most visually similar to the claimed design.” In re Jennings, 182 F.2d 207 (CCPA 1950). However, the court cautioned against bright-line rules, stating it declined to “delineate the full and precise contours of the analogous art test for design patents” because “[r]igid preventative rules [] deny factfinders recourse to common sense.” 2024 WL 2280728 at *4 and *9 (citations omitted). The court further cited a 1956 decision holding that “[t]he question in design cases is not whether the references sought to be combined are in analogous arts in the mechanical sense, but whether they are so related that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.” In re Glavas, 230 F.2d 447, 450 (CCPA 1956).

Factor two looks to the Egyptian Goddess test, focusing on the “overall appearance of the design” from the perspective of an ordinary designer in the field of the article of manufacture. Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 676 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc); Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elects., Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Under factor three, a “designer of ordinary capability who designs articles of the type presented in the application” must have some record-supported reason (without hindsight) to modify the primary reference with the feature(s) from the secondary reference(s) to create the same overall appearance as the claimed design. In re Nalbandian, 661 F.2d 1214, 1216 (CCPA 1981); Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus, Inc., 10 F.4th 1268, 1275 (Fed. Cir. 2021); Hupp v. Siroflex of Am., Inc., 122 F.3d 1456, 1462 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

Finally, the fourth factor remains a catch-all category that is highly fact dependent. The court explicitly mentioned a few potential factors, such as “commercial success, industry praise, and copying” and stated it is “unclear whether certain other factors such as long felt but unsolved needs and failure of others apply in the design patent context.” 2024 WL 2280728 at *11.

This ruling has the potential to drastically change how design patents are viewed and prosecuted and could open the floodgates for invalidation proceedings against design patents. For example, if asserting a design patent in litigation, the validity of the design patent is almost certain to be challenged in response to an infringement claim. Further, because the Federal Circuit reiterated on numerous occasions that there should be a fact-intensive determination rather than a rigid analysis or bright-line rule, there is significant ambiguity in how this case and its new standard may or may not be applied moving forward. Only time will tell.

If you are interested in bolstering your design patent portfolio, concerned about the validity of your current design patent portfolio, interested in potentially challenging another design patent, or have any other design patent-related questions, please reach out to the authors or any attorney with Frost Brown Todd’s Intellectual Property Practice.