This was originally published in Reuters Legal News (August 3, 2023).

Over the past year, rising interest rates have resulted in a significant curtailment of both fixed and floating-rate commercial real estate lending activity. Although the current interest rate environment is comparatively favorable when viewed through a long enough historical lens, the rapidly increasing costs of money and hedging products (such as interest rate protection agreements) are causing sticker shock among borrowers.

Many borrowers who are not immediately facing loan maturities and have the flexibility to temporarily forgo transacting are choosing to take a step back in hopes that rates will soon decline, or at least stabilize.

What does this all mean for the future of the lending landscape in the commercial real estate industry? This is the first in a series of articles that will set the stage as to how interest rates impact lending, explore rate cap agreements on floating rate loans and related loan document analysis and obligations, evaluate legal implications of increasing interest rates, and analyze recent bank failures and their impact on financial markets.

Market Overview: Setting the Stage

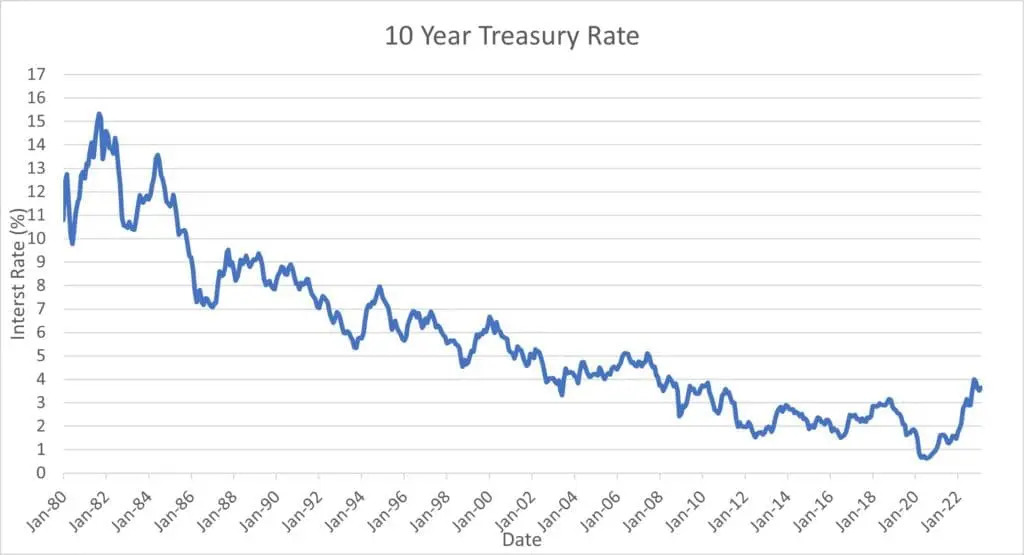

As of this writing, the 10-year Treasury yield, which generally correlates with fixed-rate loan pricing, is around 3.9%. When combined with the average spread tacked on by lenders, this results in all-in interest rates for 10-year commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS) loans (as an example of primarily fixed-rate lending) that can approach 6.5%, depending on property type and other deal-specific factors.

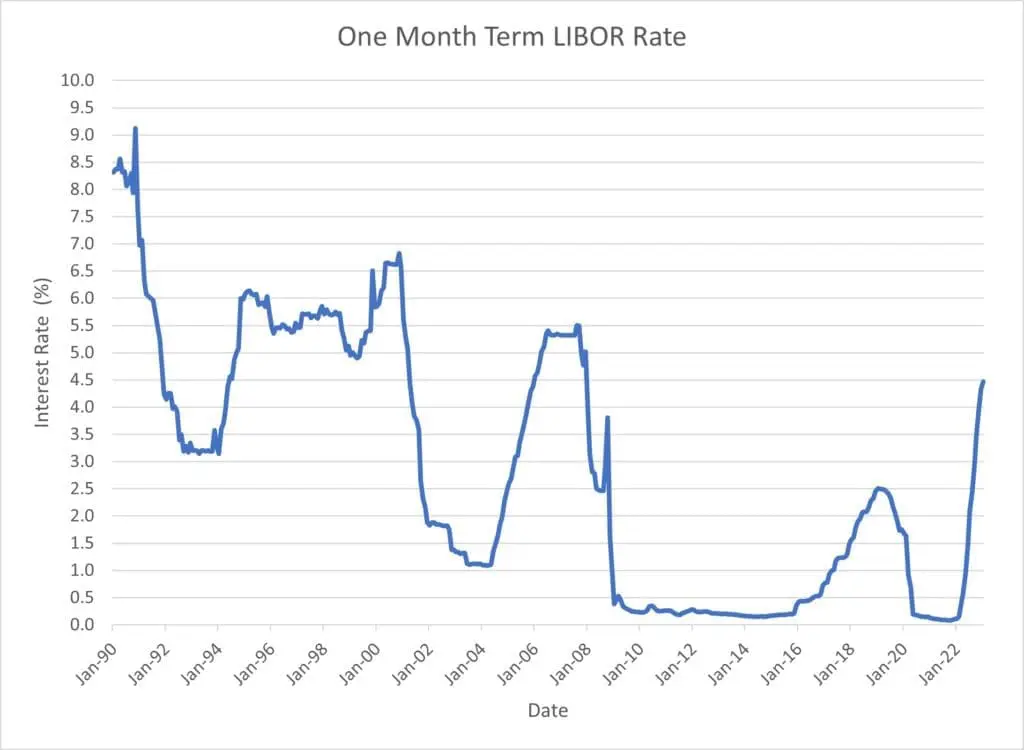

As of this writing, the one-month term Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), a common benchmark for floating rate loans (recently replacing the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) in that role), is 5.06%. After applying spreads, this results in all-in interest rates for floaters that can approach the high 7.0% range. Compare these rates to early 2022 when, thanks to a Treasury yield of less than 2% and a one-month term SOFR rate of 0.05%, all-in rates for fixed and floating rate loans were in the 4 to 5% range.

Although interest rates have risen rapidly over the past year, they are not particularly high in a historical context, as illustrated in the charts below. When the Federal Reserve was combatting inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, mortgage rates rose to an all-time high of over 18%, and the early 2000s saw rates over 8.5%. However, the low rates that persisted throughout the 2010s in the wake of the Great Recession, and the all-time low rates that followed the COVID-19 pandemic, have made the recent hikes seem comparatively dramatic, and that perception may be contributing to their chilling effect.

Impact on Underwriting

The increased debt service payments resulting from higher interest rates are creating challenges from an underwriting perspective. In most instances, increases in property incomes have not kept pace with the cost to borrow. It is therefore more difficult for properties to achieve the debt service and debt yield hurdles that lenders require.

Those deals that are still getting done are seeing reduced loan proceeds, added structure like debt service reserves and active cash management systems, and shorter terms reflecting the hope of many borrowers that rates will drop in the coming few years. Borrowers are also requesting greater flexibility to prepay their loans to take advantage of opportunities to refinance if rates begin to decrease prior to their maturity dates. All this to say that the underwriting process is more important than ever and a thorough legal review of loan terms is critical for both lenders and borrowers to protect their interests.

New Cost of Hedging Products

Another consequence of rising interest rates specifically impacting the floating rate lending market is the upsurge in the cost of hedging products, such as interest rate protection agreements. Interest rate protection agreements, which are essentially insurance policies that pay out if the identified benchmark (typically SOFR) exceeds a certain level (i.e., the “strike rate”) during the term of the agreement, are commonly required by floating-rate lenders as a condition to making a loan.

As SOFR rates continue to rise, the counterparties (i.e., the insurance providers) under these agreements are increasingly being forced to pay out large sums, which has caused the price of these hedging products to skyrocket. Reports estimate that the average cost to buy an interest rate protection agreement is 10 times greater today compared to a year ago.

Impact on Commercial Lenders

The total of the factors described above has been a precipitous decline in commercial lending activity. Compared to 2021, the Commercial Mortgage Alert reported CMBS issuance dropped by around 36% in 2022 to $70.2 billion, and commercial real estate collateralized loan obligation (CRE-CLO) issuance, as an example of primarily floating-rate lending, dropped by around 33% in 2022 to $30.3 billion as inflation continues to ease. Interest rates have begun to stabilize, which has resulted in a slight increase in lending activity in the second quarter of 2023.

However, the Federal Reserve has signaled that there may be a few more rate hikes coming before the end of 2023, which could continue to forestall the return of a vibrant commercial lending market.

What About Borrowers?

In the meantime, with an estimated $162 billion of securitized commercial mortgages reaching maturity in 2023 according to Cred IQ, many borrowers will likely seek extensions or modifications of their existing loans in hopes of temporarily preserving more favorable interest rates. However, similar to the requirements for new loans, lenders will likely want reserves, cash management systems or other added structure in exchange for such extensions or modifications. Such demands may be unpalatable to borrowers with properties that are otherwise performing well under their current loan terms.

Where extensions or modifications of maturing loans are unworkable, borrowers may be forced to seek alternative sources of financing, and in some cases will face defaults and workout scenarios. There is some potential for acquisition financing activity as property owners may be forced to sell if refinancing options are not viable, though purchasers will face the same challenges obtaining loans, which could result in reduced purchase prices.

Conclusion

In the year’s second half, rate increases will continue to plague the commercial real estate industry. To navigate this volatile period, lenders and borrowers will need to be creative to secure mutually beneficial loans. This series will review related legal implications and more in upcoming articles.

For more information, please contact any attorney with Frost Brown Todd’s Financial Services industry team.

The Carveout

A legal blog geared toward sophisticated capital market participants, The Carveout provides insight into current trends and developments in commercial real estate finance (CREF)—with a particular focus on non-recourse carveouts and CREF loan platforms including CMBS, debt funds, private capital, REITs, life insurance companies, and other complex sources of capital.